Special Edition from the Office of the CIO: Inflation

The government admits inflation is not transitory – now what?

High inflation has been a theme for more than two years, and now CPI numbers have finally caught up. I recently talked rather extensively about this development with Peter McCormack back in October, if you want to listen.

I first started warning about it in early 2020, given the convergence of money printing and impeding supply chain issues, if you want to read or listen to the reasoning:

Despite excuses for higher housing, energy, gasoline, and food prices, inflation continues, and will continue to rise. The Federal Reserve has finally admitted this situation is not transitory and has taken actions many expected far earlier than now.

- The central bank announced an accelerated tapering of the bond buying program through March, and

- signaled the possibility of three rate hikes this year alone.

These moves are welcomed by many but the reality is that they have come far too late in order to fight current inflationary pressures.

Inflation takes a long time to sink in

For 12 years, the Fed has been growing its balance sheet by buying US Government assets while the Treasury has been printing money to offset the lower velocity of money present during the last financial crisis. Sure, there has been inflation that entire time, but it was closer to the 2-3% target set by the Fed. Put more simply, it took more than a decade for real inflation to take hold.

One of the reasons we did not have the level of inflation expected over this time, especially during the early days of the pandemic’s onset, was wage growth, which is a primary driver of higher prices – goods and services are likely to sell for more, and more of them will be sold if people can afford to purchase them. Most people know and understand the Phillips Curve, which explains the inverse correlation between the rate of change in unemployment and inflation, but more accurately, the rate of change in nominal wages is also a factor.

Wage growth really began about two years ago, during government programs to deliver stimulus checks to people who were not permitted to work as lockdowns went into effect. Often, people made more money to not work than they did to work. This caused more disposable income while simultaneously drying up the labor pool, causing companies to have to increase wages to entice more people to come to work. Many in government have tried for years to increase the minimum wage to $15/hour, and we effectively got an increase to $20/hour through stimulus-related economic policies.

Increased wages, increase inflation

The various stimulus and money printing policies pumped equities markets as millions of people stuck in their homes turned to trading apps like Robinhood to pass the time. When equities markets are higher, consumer confidence goes with them, but we will come back to that later.

Will the change in fed policies work to tamper inflation? Maybe, and eventually.

If it took 10 years of loose monetary policy to create inflation, it could take that long (or potentially longer) to undo these effects. Remember that tapering isn’t unwinding of the balance sheet, it is just adding to the balance sheet at a slower pace, until they stop adding in March.

Also, with three rate hikes still likely, short-term yields are likely to remain less than one percent, and the 10 year yield would probably still remain lower than three percent. Historically, that falls short of average yields. This form of monetary policy is still too loose to attack inflation, which currently stands at 7.5%. We also run the risk of desired effects not occurring as soon as many would like, leaving inflation with us for an extended period of time

Where do we go from here?

“Central bankers always try to avoid their last big mistake. So every time there’s the threat of a contraction in the economy, they’ll over stimulate the economy by printing too much money. The result will be a rising roller coaster of inflation, with each high and low being higher than the preceding one.” – Milton Freidman

There are a lot of predictions out there on when rate hikes will begin and how many we will get this year, but here is what I believe the most likely path is.

The next FOMC meeting is in March, which is when tapering ends, and the balance sheet will go flat in nominal terms instead of increasing. At that meeting, rather than announce an immediate rate hike, the Fed will likely attempt to tame market volatility by announcing that the first rate hike will occur at the May FOMC meeting. The first rate hike will already be priced in, and the Fed will expect smooth markets as new hikes are slowly priced in as well.

They will also likely announce that, after March, all cash proceeds from maturing Mortgage Backed Securities (MBS) will not be used to buy additional securities, and will instead simply roll off the balance sheet. We do not anticipate this will be the case for Treasuries, though, which will probably lead to a measured shrinking of the balance sheet without causing long-term rates to spike too much.

The effects of this plan, should they come to pass as described above, are likely to be

- Inflation will still be a problem, and CPI would continue to rise, particularly from rents

- Financial markets are likely to slowly sink into May and the summer, then slowly begin recovering in September (a “U” shape).

Emerging housing issues

Regarding rents, there are several factors at play. First, hard assets gain value in an inflationary environment, and real estate will continue to be in high demand, posting 10%+ gains year-on-year.

Additionally, large asset managers are continuing to purchase single family homes in bulk for both price appreciation and to earn income on rents since the bond market has a negative real return. If the houses don’t rent for the expected income return, they will simply sit vacant until they do, creating less inventory.

And, finally, with interest rates going up, mortgages become more expensive, forcing smaller landlords to charge higher rent. This is likely to contribute to higher CPI in the short term.

Commodities

Commodities are also in a unique position, as they are both affected by continual inflation and are in low supply to demand. If you look at the futures markets in most commodities, you will see a swing towards backwardation, which usually paints a higher price picture. Expect wheat, cotton, natural gas, and other common commodities to cost more with continued wage growth, supply chain issues, and, of course, global money printing coming home to roost.

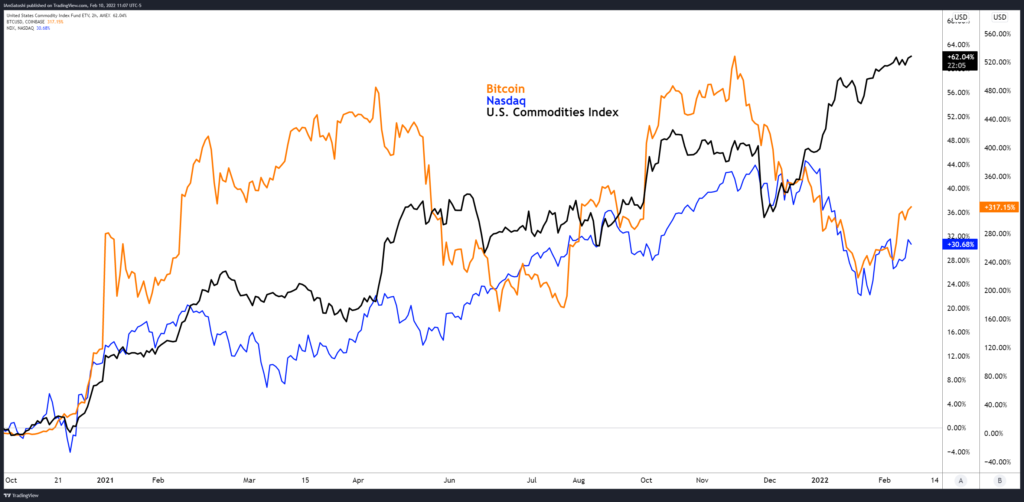

Bitcoin, with its limited supply and liquidity, will be used by many traders as a stand-in to purchase inflation. Bitcoin has been more correlated to equities in the last few months, but I see that correlation shifting towards commodities in the near-term. Needless to say, inflation is the tide that will lift these boats.

https://www.tradingview.com/x/BW5Hx7z7/

The Portfolio Management Team

Steven McClurg, CIO

Bill Cannon, Portfolio Manager

Wes Cowan, Portfolio Manager, Head of Defi

Josh Olszewicz, Head of Research

Sean Rooney, VP Research and Trading

Will McDonough, Vice Chairman, Investment Committee

Leah Wald, CEO, Investment Committee

Shannon Smith, Head of Investor Relations